MONTICELLOVIRGINIA |

|

MONTICELLOVIRGINIA |

|

|

|

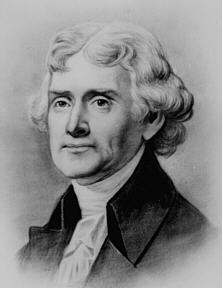

Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello Monticello, meaning “little mountain,” was designed and built by Jefferson over a period of 40 years. One of our country’s foremost architectural masterpieces, Monticello remains a testimony to its creator’s ingenuity and diverse interests. The main house and gardens reflect the innovative character of their designer, while Mulberry Row offers insights into plantation industries and workers, both slave and free. (Monticello Marker) |

Jefferson began constructing his Monticello, “little mountain,” home in

1768. About the same time, he became a member of the Virginia House of

Burgesses, which met in Williamsburg (an upcoming site on this road trip).

At the beginning of the Revolutionary War in 1775, Jefferson was a member of the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia. It was there that he was drafted to write the Declaration of Independence, which was ratified with many revisions on July 4, 1776.

In 1779, Jefferson became Governor of Virginia. A year later,

the capital was moved closer to his Monticello home from Williamsburg to

Richmond (also an upcoming site on this road trip).

In 1779, Jefferson became Governor of Virginia. A year later,

the capital was moved closer to his Monticello home from Williamsburg to

Richmond (also an upcoming site on this road trip).

While serving as Governor during the British second invasion of Virginia in January 1781, Jefferson received a letter from Benedict Arnold offering to spare Richmond if he was allowed to seize tobacco unmolested. Jefferson refused and Arnold ransacked Richmond.

On June 4, 1781, Jefferson was entertaining the Speaker of the Virginia Assembly when he was warned about Tarleton’s raid in Charlottesville. Jefferson made his escape by horseback barely minutes before Tarleton’s arrival.

Near the end of the war, Jefferson’s wife, Martha, passed away. Two years later, Jefferson began service as trade commissioner and minister to France. He returned in 1789 with new ideas about architecture and set-about redesigning Monticello. The redesign, with European influence, continued throughout his service as the third president of the United States and was largely completed when he returned from public service in 1809. Jefferson died here at Monticello on July 4, 1826, exactly fifty years after the signing of the Declaration of Independence.

Today, Monticello is a magnificent legacy to Jefferson. Led by a tour guide, visitors begin their tour at entrance hall, an impressive two-story room that also served as Jefferson’s museum. It is crowded with a wide variety of objects that he collected from all over the world. From the entrance hall, visitors are led through his library, bedroom, parlor, dining room and guest bedrooms. During the tour, visitors gain a great appreciation for the many talents and service of Thomas Jefferson.

|

|

Life on Mulberry Row Both black and white laborers lived and worked on Mulberry Row. Jefferson hired free white artisans to train his slaves, many of whom became highly skilled blacksmiths, carpenters, coopers, masons, charcoalburners, shoemakers, and weavers. Jefferson provided each black family with a small dwelling, weekly rations of corn and pork, and summer and winter clothing. After their long work day (usually sunrise to sunset) and on Sundays and holidays, the Monticello slaves often supplemented their basic allotments by hunting, fishing, tending their gardens and poultry yards, or performing additional paid tasks. (Monticello Marker) |

Mulberry Row was “main street” Monticello. Along this street were workmen's homes, gardens, a smokehouse/dairy, a blacksmith shop/nailery, a joinery, a carpenter’s shop and sawpit. Mulberry Row is evidence that Monticello was not only home to Thomas Jefferson, but was also a community employing over a hundred slave/artisans. Although Jefferson called slavery “an abominable crime,” he was trapped by the economics of the institution and was a slaveholder his entire life.

|

The Monticello Graveyard This graveyard had its beginning in an agreement between two young men, Thomas Jefferson and Dabney Carr, who were schoolmates and friends. They agreed that they would be buried under a great oak which stood here. Carr, who married Jefferson’s sister, died in 1773. His was the first grave on this site, which Jefferson laid out as a family burying ground. Jefferson was buried here in 1826. The present monument is not the original, designed by Jefferson, but a larger one erected by the United States in 1883. Its base covers the graves of Jefferson, his wife, his two daughters, and Governor Thomas Mann Randolph, his son-in-law. The graveyard remains the property of Jefferson’s descendants, and continues to be a family burying ground. (Monticello Marker) |

The Monticello Graveyard was laid out by Jefferson prior to the Revolutionary War and continues to be a family burying ground today. Over Jefferson’s grave is a monument inscribed as he had instructed noting the three accomplishments of which he was most proud: (1) Author of the Declaration of Independence, (2) Author of the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom and (3) Father of the University of Virginia.

Colle -- Colle is where General Baron von Riedesel and his wife, Baroness Riedesel, were held as prisoner/guests after the British prisoners of Saratoga were moved from Boston to Charlottesville. The general led the prisoners in their march from Boston and dined with Lafayette on the way. After suffering from heat stroke, he was the subject of a prisoner exchange and returned to duty in British-held New York City in late 1779.

|

|

Colle The house was built about 1770 by workmen engaged in building Monticello. Mazzie, an Italian, lived here for some years adapting grape culture to Virginia. Baron de Riedesel, captured at Saratoga in 1777, lived here with his family, 1779-1780. Scenes in Ford’s novel, Janice Meredith, are laid here. Conservation & Development Commission 1928 (Route 56 Marker) |