KINGS MOUNTAINSOUTH CAROLINA |

|

KINGS MOUNTAINSOUTH CAROLINA |

|

Kings Mountain is an isolated high ridge near the border of North Carolina.

Named for an early settler, the mountain is a rocky spur of the Blue Ridge that

rises 150 feet above the surrounding area. Its forested slopes, sliced with

ravines, leads to a summit, which in 1780 was nearly treeless. This plateau, 600

yards long by 60 yards wide at the southwest end and 120 yards at the northeast

end, gave Lieutenant-Colonel Patrick Ferguson a seemingly excellent position for

his army of about 1,100 Loyalists.

The Patriots arrived in the early afternoon of October 7, 1780 at the foot of the mountain. They had ridden through a night of rain with their long rifles protected in blankets. The rain had muffled their sounds, giving Ferguson little warning of their approach.

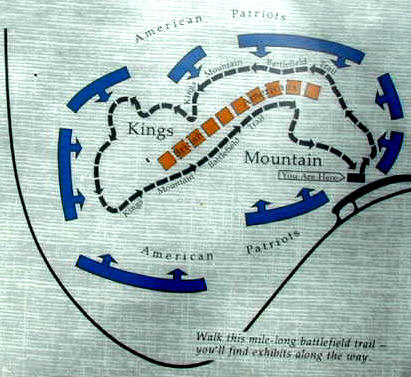

After the rain stopped falling, the Patriots with a select army of about 900 of their best riflemen prepared for an immediate attack. The men hitched their horses within sight of the ridge, divided into two columns, and encircled the steep slopes.

Isaac Shelby and William Campbell took their men to an area below the southwest end of the ridge. The remainder, under Benjamin Cleveland, John Sevier and Joseph McDowell, moved to the northeastern foot of the ridge. Ferguson's outlying posts were taken by surprise and no warning reached the Loyalists on top of the hill. After silencing the Tory pickets, the Patriots advanced with a war whoop, heading straight up the difficult slope.

|

Shelby’s Colonel Shelby’s Overmountain Men were in the thick of battle from start to finish. Long before other Patriot columns had reached their positions, Ferguson’s Provincials and Loyalists had opened fire on the mountaineers and Campbell’s Virginians. Three times Shelby’s men were repulsed. Still they came on until Kings Mountain was theirs. (Kings Mountain Marker) |

|

The Loyalists rained down a volley of musket fire, but the forested slopes provided good cover for the attackers. The Patriots, skilled at guerrilla tactics used on the frontier, dodged from tree to tree to reach the summit. Twice, Loyalists drove them back with bayonets. Finally the Patriots gained the crest, pushing the enemy towards the Patriots who were attacking up the northeastern slopes. Surrounded and silhouetted against the sky, the Loyalists were easy targets for the sharpshooters and their long rifles.

The battle at Kings Mountain is unique in that many of the Patriots were armed with rifles that shot more accurately. Their opponents, on the other hand, were armed with muskets and bayonets. Another tactical advantage that the patriots had is that men shooting uphill are more likely to hit their mark, while men shooting downhill tend to fire too high. As the Loyalists charged, they were exposed to rifle fire at close range. While Loyalist bayonet attacks were temporarily successful, the Patriots simply moved back, and took cover behind rocks and trees, and then returned to battle.

When the Patriots fought their way onto the mountain top. They found a clear vista that was advantageous to their aimed rifles. The Loyalists were almost helpless in the face of such destructive fire.

|

Retreat and Surrender The Patriot forces relentless advance from all sides of the mountain soon drove the British back to the northeastern end of the ridge. There, amid the confusion of the battle’s final moments Ferguson’s beaten troops made several attempts to lay down their arms before the victorious Patriots finally accepted their surrender. (Kings Mountain Marker) |

|

While attempting to rally his men for a charge through the encircling riflemen, Ferguson was shot down. He fell, one foot caught in a stirrup. His men helped him down and propped him against a tree, where he died. Captain DePeyster, Ferguson's second-in-command, ordered a white flag hoisted but, despite Loyalist cries of surrender, the Patriot commanders could not restrain their men. Filled with revenge and yelling “Tarleton’s Quarter,” they continued to shoot their terrified enemy for several minutes, until Campbell finally regained control.

|

To the memory of Col. Patrick Ferguson Seventy-First Regiment Highland Light Infantry. Born in Aberdeenshire, Scotland in 1744. Killed, October 7, 1780 in action at Kings Mountain while in command of the British Troops. A soldier of military distinction and of honor. This memorial is from the citizens of the United States of America in token of their appreciation of the bonds of friendship and peace between them and the citizens of the British Empire. Erected, October 7, 1930. (Kings Mountain Marker) |

|

During the battle, about 300 Loyalists were killed and the remainder were taken prisoner. Cornwallis’ hope for maintaining control over the Backcountry using Loyalist militia was now dashed. Kings Mountain was the turning point of the Southern Campaign of the Revolutionary War.

Today, the park commemorates this pivotal and significant victory by Patriot militia over Loyalist forces. The Visitor Center includes many exhibits and in the theatre, the film, “Kings Mountain: Turning Point in the South,” is shown frequently. Outside the Visitor Center is a three-mile battlefield trail that travels along the north slope of the mountain then traverses the summit. Markers and monuments can be found at many sites along the trail.

|

To commemorate the victory of Kings Mountain October 7, 1780, erected by the government of the United States to the establishment of which the heroism and patriotism of those who participated in this battle so largely contributed. (Kings Mountain Marker) |

|

The park is open daily from 9AM-5PM, except Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Year's Day.