BRANDYWINEPENNSYLVANIA |

|

BRANDYWINEPENNSYLVANIA |

|

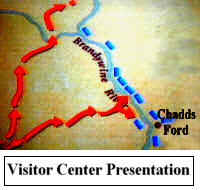

On September 9th, Washington chose this high ground in the area of Chadds Ford to defend against the British invasion from the Chesapeake. Chadds Ford allowed passage across the Brandywine Creek on the road from Baltimore to Philadelphia. Washington placed his troops along the Brandywine Creek to guard the main fords. With detachments at the southernmost and northernmost crossings of the creek, Washington hoped to force a fight at Chadds Ford, an advantageous position for the Americans. The closest unguarded ford was twelve miles up the creek. Washington was confident in the American defensive preparations.

The

British march halted at nearby Kennett Square and Howe formulated a plan. His

plan had a portion of the British army marching from Kennett Square and faking a

main attack on Washington at Chadds Ford. The majority of the army would march

beyond Washington’s northernmost defensive position, cross the creek and

attack the American forces on their flank. Washington was not prepared for this

battle plan.

The

British march halted at nearby Kennett Square and Howe formulated a plan. His

plan had a portion of the British army marching from Kennett Square and faking a

main attack on Washington at Chadds Ford. The majority of the army would march

beyond Washington’s northernmost defensive position, cross the creek and

attack the American forces on their flank. Washington was not prepared for this

battle plan.

On September 11th, the battle began with a heavy fog that blanketed the area, providing cover for the approaching British troops. When the fog cleared, the sun blazed and the heat was sweltering. The first reports of British troop movements indicated to Washington that Howe had divided his forces. Subsequent reports were confused and Washington persisted with the belief that the British were sending their entire force against his line at Chadds Ford.

|

Battle of Brandywine On Sept. 11, 1777, an American force of about 11,000 men, commanded by Washington, attempted to halt a British advance into Pennsylvania. The Americans were defeated near Chadds Ford on Brandywine Creek by approximately 18,000 British and Hessian troops under Howe. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. (Brandywine Marker) |

|

Meanwhile, Howe and the majority of his force continued their approach on Washington’s right flank. By mid-afternoon the British had crossed the creek at the unguarded fords to the north of Washington's force and they had gained a strategic position on Washington’s right flank.

A

British officer who was with the flanking forces recorded the following:

A

British officer who was with the flanking forces recorded the following:

“A rapid march from four o'clock in the morning till four in the eve .. There was a most infernal fire of cannon and musketry. Most incessant shouting. 'Incline to the right! Incline to the left! Halt! Charge!' etc. The balls plowing up the ground. The trees cracking over one's bead. The branches riven by the artillery. The leaves falling as in autumn by the grapeshot.”

Washington realized that he had been outmaneuvered and ordered his forces to take the high ground as a last defense. At 4 PM, Howe launched a bayonet attack into a gap in Washington’s flank. Troops under General Nathaniel Greene raced in to counter the attack, but in the melee that resulted the Americans began to fall back. In the confusion, they gradually fell into full retreat and the British took the battlefield, but they failed to pursue. Instead, Howe’s exhausted forces camped on the battlefield and in the surrounding countryside while Washington’s forces regrouped north of Chadds Ford in Chester.

|

Casimir Pulaski Polish volunteer, commanded cavalry detachment helping to cover Washington’s retreat from Brandywine, September 11, 1777. As brigadier general, served September 1777 - March 1778 as first overall commander of the Continental Army’s cavalry. He was mortally wounded at the siege of Savannah, October 9, 1779. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission (Brandywine Marker) |

|

Today, a portion of the Brandywine Battlefield is maintained by state of Pennsylvania. Three buildings and picnic grounds can be found the on the battlefield. In the Visitor Center, the Battle of Brandywine and the American Revolution are presented through interpretive exhibits and an audio-visual presentation. They tell the story of the battle and its relation to the British invasion from the Chesapeake.

The

home of Benjamin Ring, a Quaker farmer and miller, was Washington’s

Headquarters on the eve of the Battle of Brandywine. Washington used the house,

which is a short distance from Chadds Ford, to hold a council of war with his

generals and to plan his strategy. During the 20th century, the house fell into

disrepair, and was extensively damaged by fire in the early 1930's. Today, it

has been reconstructed and visitors can see it much as it was during the

battle.

The

home of Benjamin Ring, a Quaker farmer and miller, was Washington’s

Headquarters on the eve of the Battle of Brandywine. Washington used the house,

which is a short distance from Chadds Ford, to hold a council of war with his

generals and to plan his strategy. During the 20th century, the house fell into

disrepair, and was extensively damaged by fire in the early 1930's. Today, it

has been reconstructed and visitors can see it much as it was during the

battle.

The home of Gideon Gilpin, also a Quaker farmer, was the headquarters of the Marquis de LaFayette. The Battle of Brandywine was his first military action in America with Washington. After the battle, Gilpin's property was plundered by foraging soldiers. The claim for losses filed by Gilpin provides insight into the prosperity of this farm. The claim included: 10 milk cows, a yoke of oxen, 48 sheep, 28 pigs, 12 tons of hay, 230 bushels of wheat, 50 pounds of bacon, a history book, and a gun. Today, the house appears much as it was in 1777 when the famous French patriot was quartered here.

Although the American army was forced to retreat after the Battle of Brandywine, the defeat did not demoralize them. Washington made the following report to Congress:

Notwithstanding the misfortune of the day, I am happy to find the troops in good spirits.

In the Battle of Brandywine, they learned that they could meet and fight the British on the battlefield. They blamed the defeat on poor reconnaissance.

At about a quarter mile from US Route 1, you’ll reach the Chadds Ford Museum and John Chad's House.

|

John Chad’s House

Having fallen heir to his father’s five hundred acre “plantation” along the Brandywine, John Chad was already a man of some importance when he had a house built on the banks of the creek, probably by John Wyeth, Jr. The house’s style and appointments suggest moderate wealth; its simplicity reflects Chad’s Quaker heritage. In 1729, about four years after the house was completed, Chad took Elizabeth Richardson as his bride and this became their home. By 1736, Chad had successfully petitioned for a license to operate a tavern and, about the same time, began a ferrying service. Chad leased both businesses to a relative in the 1740s. Although the village bears John’s surname, perhaps the house should be referred to as Elizabeth’s, for she was at home here for over 60 years. John died in 1760, leaving his widow the use of the house and forty acres of land. Elizabeth stood fast at the time of the Battle of Brandywine, September 11, 1777, hiding “her silver spoons daily in her pocket.” The widow Chad reportedly observed Hessian and Continental troop movements from the attic window which you see. Today, the house’s pleasing proportions and continuous cornice, and its original oak floors, paneling, and woodwork make it a fine example of the early 18th century Pennsylvania architecture. Its prime location on the hillside dictated it be built as a bank house. When the house is open for tours, a guide in colonial garb demonstrates the domestic art of bread baking in the brick lined oven. During summer weekends, some 1,000 loaves of bread are baked here, and visitors are offered samples. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the Chad’s House is the anchor in the Chadds Ford Village Historic District. The Chad’s House is also a contributing element of the Brandywine Battlefield National Historic Landmark. The John Chad’s House is open weekends May through September, noon to 5:00 p.m. (Brandywine Marker) |

At about two and a half miles past Route 100, you’ll reach a marker that indicates where Cornwallis out-flanked the American position.

|

Battle of Brandywine The British attack on the American right wing began here late in the afternoon. After heavy fighting, the defense line which Sullivan formed hastily near Birmingham Meeting House was forced to retreat to Dilworthtown, 2 miles southeast. Reinforcements from Chadds Ford delayed the British as Sullivan’s men fell back. Pennsylvania Historical and |

|

During the next several days after the Battle of Brandywine, General Howe and his Army moved closer to Philadelphia with little opposition from Washington. The two armies maneuvered in hopes of finding the other at a disadvantage, but no decisive military actions were taken during the next two weeks. Congress abandoned Philadelphia and moved first to Lancaster and then to York to escape before the British takeover. Important military supplies were moved out of the Philadelphia area to Reading, Pennsylvania. On September 26th, a column of British soldiers marched into the patriot capital unopposed.

Depart the Brandywine Battlefield.

Malvern -- After the American retreat at the Battle of Brandywine, the American’s prepared to do battle with the British once again in this area near Malvern. However, a giant cloudburst terminated the confrontation when the rain destroyed hundreds of thousands of gunpowder cartridges. Once again defeated, this time by Mother Nature at the “Battle of the Clouds,” the Americans retreated to Reading for resupply.

Great Valley House, Circa 1720 -- The house is a

B&B and one of many 18th century homes that you’ll find in the area.

Great Valley House, Circa 1720 -- The house is a

B&B and one of many 18th century homes that you’ll find in the area.

Lord Stirling’s

Headquarters -- Many nearby homes and farmhouses became quarters for

general officers during the encampment. Political feelings in the area were

divided, with most residents wishing to be left free from the conflict. The

occupation of Valley Forge ended that wish and brought the war to their

doorstep. Some officers quarters still stand, although most of these have been

altered over the years. Some are included in the park tour; others are not open

to the public.

|

Quarter of Major General William Alexander Lord Stirling, Continental Army during the Valley Forge encampment, December 19, 1777 - June 19, 1778. Major James Monroe fifth president of the United States also quartered here as Aide-de-Camp to Stirling. Home of Parson William Corrie. Erected by the Pennsylvania Society Sons of the Revolution, December 19, 1975 (Valley Forge Marker) |

|

Covered Bridge.

Covered Bridge.

Washington Memorial Chapel and Valley Forge

Historical Society Museum -- The chapel and museum are located on private property

within the historical park and belong to the Episcopal Church. Visit the

beautiful chapel and look at the many Revolutionary War artifacts in the museum.

Washington Memorial Chapel and Valley Forge

Historical Society Museum -- The chapel and museum are located on private property

within the historical park and belong to the Episcopal Church. Visit the

beautiful chapel and look at the many Revolutionary War artifacts in the museum.

Behind

the museum is the Martha Washington Log Cabin. Housed in the cabin is the Chapel

Cabin Shop, which is a gift shop and restaurant. The restaurant is a great place

for a home-cooked lunch. Be sure to order the soup.

Behind

the museum is the Martha Washington Log Cabin. Housed in the cabin is the Chapel

Cabin Shop, which is a gift shop and restaurant. The restaurant is a great place

for a home-cooked lunch. Be sure to order the soup.

Schuylkill River -- The river, as well as the stream that passed under the covered bridge, are geographic barriers that, in part, make Valley Forge a good area for the American encampment.

| Park Photos courtesy of Brandywine Battlefield Park |